The first national building workers strike was one of a large number of industrial disputes in 1972. They included miners, steelworkers, car workers and dockers. These disputes had been successful for the unions involved and demonstrated the power and effectiveness of collective action by trade union members.

1972 saw the highest number of strike days in Britain since the General Strike in 1926. The Tory government called two States of Emergency. The first was in February 1972 during the miners’ strike. 15,000 trade unionists, including coal miners and local engineering workers closed the gates of Saltley coke depot in Birmingham. The second was in August 1972, during the dockers dispute. The Conservative Government tried to use the Industrial Relations Act 1971 to emasculate the unions’ ability to defend members’ wages and conditions of employment. Most unions refused to recognise the provisions of the Act thus making it ineffective.

It was different for the unions involved in the building dispute. Their national strike was unique because it was more difficult for building workers unions to organise workers in the industry. Building sites were, by their nature, temporary and geographically dispersed. They were operated by different employers depending upon which one had won the contract for the construction work, whether it was for houses, a factory, a hospital or an office block. Each new site often brought together a group of workers who had not worked regularly with each other and who had to negotiate afresh with the employers over rates of pay and conditions of work. Sites where “lump” workers were working proved difficult for the union members to organise. The “lumpers” weakened the unions’ negotiating strength with the employers.

On any given building site there were a large number of different trades, many in separate, small unions: electricians, carpenters, painters & decorators, plasterers, bricklayers, plumbers, labourers, scaffolders, steel fixers etc..

When a building site finished, the process of negotiating new pay and conditions started all over again on the next one. The construction employers’ blacklist ensured that active trade unionists were not hired on new sites.

The building workers trade unions formed the operatives side of the National Joint Council for the Building Industry (NJCBI). They agreed to submit a pay-claim to the employers side of the NJCBI of £30 per week and a basic 35-hour week for all trades.

The employers rejected these demands and in May 1972 the trade unions called a national selective strike. The unions decided that they would call out members first on the bigger and better-organised sites from 26 June. These were in the main towns and cities such as London, Liverpool, Birmingham, Manchester and Newcastle.

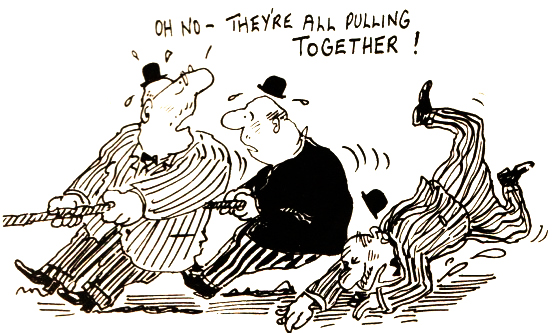

Some employers conceded the claim but the unions wanted to establish the principle that members throughout the country would be paid the same rate. An all-out strike was called in August and union members began to organise flying pickets to go to sites, usually in small towns and rural areas, which were still working. The flying picket proved to be a successful tactic. Instead of picketing sites where everyone had supported the strike and stopped working, union members decided to picket sites in smaller towns and other areas where support was not as strong. This proved to be very effective and the employers soon asked for further talks with the unions.

On Thursday 14 September 1972 the union side in the negotiations agreed a settlement with the employers. There would be an immediate increase in basic rates of pay of £6 per week for craftsmen and £5 per week for labourers. There was no reduction in the working week from 40 hours though.

This was the largest single pay increase ever negotiated in the building industry. It was a magnificent victory for trade union organisation, against all odds. The building trades employers, and their supporters in the Conservative Government, were shaken by this. One of the least well-organised groups of workers had taken on their employers and won.

The Conservative Government and the employers did not let matters rest there…